We’re back! The weather outside is pretty terrible, we’re ruled over by genetically engineered brains in bomb-proof bunkers, our new amphibian allies are not so friendly and our best friend is a lobotomised drone living in a glass house. It’s time for one of my favourite periods in Sci-Fi history – strap in for an anxious and deeply European time on Goonhammer Reads Science Fiction!

We’ll be looking at 1919-1939 today, a period when Scifi moved beyond the prehistoric phase of social metaphor and utopianism into the searching, meaningful and deeply weird genre we know and love. In these deep vaults of history you’ll find terrible knowledge man was not meant to know, robots challenging us on what it means to be human, thinly-veiled colonialism metaphors and an explosion of authors, themes and imaginations that birthed science fiction as we know it today. Some people call this the end of the Radium Age, or the mid-Pulp, or something similar, but I, based on nothing but a gut feeling, am going to call it The Revolutionary Age.

Foreshadowing of the Bomb

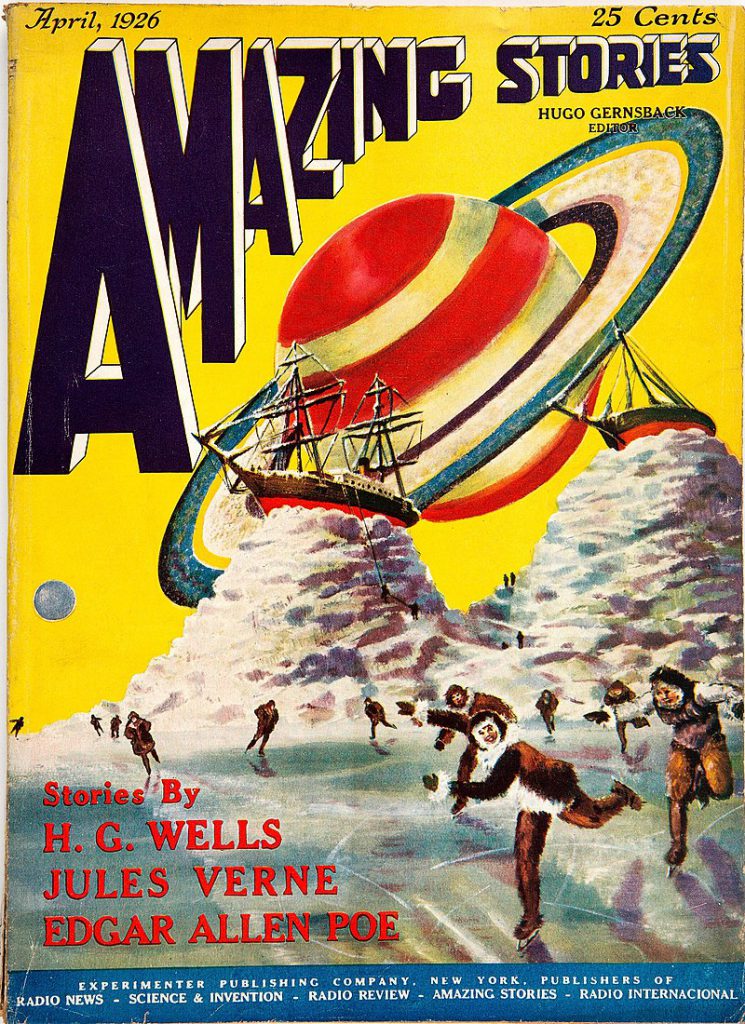

The Revolutionary Age is Scifi that has grown up out of the dream utopianism of HG Wells and Jules Verne, the millenarian-style cult of technology of Thomas Edison and Tesla and all the promise that the start of the 20th century held for those who were rich, male and white enough to enjoy it. It is bounded by a civilisation-shattering War on one end, and Hiroshima on the other. The Old World that HG Wells imagined from has died, torn apart in wars or willed into non-existence by a guy with a small beard and his Bolshevik friends, but the future – all the robots and workers, genetic theory and eugenics, a succession of terrifying revolutionary new ideas about how everything works – is very much alive. It is a period where the march of technology and social change sped up beyond comprehension. The future seemed closer, weirder, scarier and more complex than anyone writing even a few years before could have imagined, and then it ends catastrophically in the blink of an eye that opens into Oppenheimer’s new dawn.

There’s a common theme found in great revolutionary era scifi that speaks to many of our own contemporary concerns: what the hell will the future look like? In a world increasingly unrecognisable, where new systems and industries were changing the patterns of human life and some of the absolute worst pieces of shit in human history seized power, everyone was asking what the world would look like in five years, or ten years, or twenty at the most. War was coming, for sure, but what else? It took Scifi authors to project out a thousand – or in the case of one of our recommends for today – twelve billion years into the uncertain future. Scifi takes us forward into the future, good Scifi says something about it’s contemporary setting when doing so but great Scifi tells us something about what it means to be human in such times, and to look out into the great unknown void of the future and challenges us to do something about it.

If we were focused solely on America, we might not see much of that. We’d be talking about Pulp stories with tits on the cover and Edgar Rice Burroughs, Robert E Howard and C L Moore, eventually turning into positive outcomes for big brained scientist heroes solving problems. We’ll come to that, but this time is for Europe. Weird, anxious, war-torn Europe, where the 20s and 30s saw Science Fiction writers hold a mirror up to their increasingly alienating world, and create some of the all-time great works of the genre as a result.

Three Recommends in Revolutionary SF

These three recommends from the 20s and 30s show European between the wars Scifi at it’s best. They’re funny, visionary and challenging, speaking to a future that we now know exceptionally well, but lurked threateningly just over the horizon for the writers

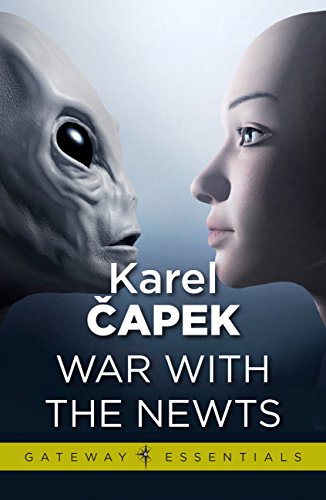

War with the Newts – Karel Capek

Intelligent Newts have been discovered near Sumatra, and immediately put to work farming pearls – but they’re clever little things, and soon they’ve picked up some funny habits, like smoking, walking about on land, organising little excursions, and making weapons. Before anyone notices that last one, the Newts have drawn up their own plan, and human societies don’t really factor into it.

Though I waxed lyrical about the forward looking 30s SF in the intro, War with the Newts is less prophetic farseeing and more writing about what’s happening on your doorstep right now holy shit we should be doing something about this. War with the Newts takes us through a madcap satirical SF comedy through a slowly building political and economic study of the rise of the Newts – cleverly told through newspaper cuttings and essays – into a utopian/postapocalyptic (depending on which side you’re one) account of the decline of humanity at the hands of their new, amphibian, masters.

Capek starts with a fairly broad brush satire of 1930s politics, very much in the vein of Hasek’s Good Soldier Svejk (which is a bloody good read in and of itself), that takes aim at US racism and isolationism, British exceptionalism and all-round bastardliness, German racial science and European colonialism before turning into a laser focus on nationalism and militarism. Capek writes (in a good translation at least) with a light touch, inventive structures and then pivots on a penny to slam the anti-militarist and anti-nationalist message home with the twist that the Nazis Newts are on their way, and it might well already be too late. It’s bloody funny too.

War with the Newts is often sold alongside R.U.R. (Rossom’s Universal Robots), a pretty great play that introduced Robots to Scifi, but to me at least it’s the better piece.

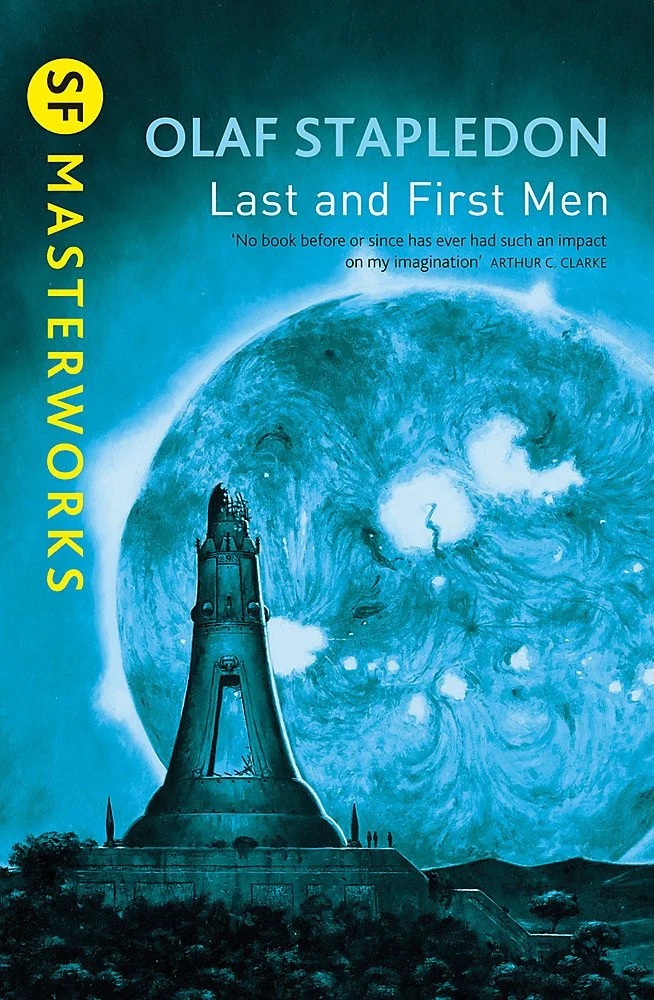

Last and First Men, Olaf Stapledon

One thing to be well aware of in Last and First Men is that it begins with a fair estimation of the several decades after publication (1930) before arriving at a two-superpower Cold War between the US and China. There is some deeply weird Orientalism at play that segues directly into some really rank racism when discussing the American Civilisation. The racism and antisemitism included in these sections is very of it’s time, but was not acceptable then or now. It is an example of a deluded and immoral “racial science” we are still, as a society, in the process of chucking in the bin where it belongs. It is deeply unpleasant to read. If, given that warning, you still want to read Last and First men you should skip to the End of the First Men and the rise of the Second and miss that out altogether.

Last and First Men plants itself firmly in 1930, looks forward at the next ten and twenty years and then takes a breath, relaxes, and dives right in. Stapledon takes you through billions of years of human evolution, four planets and 20 species, with peoples and nations rising and falling in great cycles of civilisation. Humanity grows and spreads, suffers catastrophe, moves planets, creates worlds and lives and dies as much as a species as any individual within it. Stapledon lived through one world dying in his time as a conscientious objector and ambulance driver during the First World War, and his answer to the big question of what happens next is, well, everything. That humanity will tear itself apart, be destroyed by invaders, be annihilated by changing climate or nuclear horror, or simply devolve – physically, spiritually and mentally – time and time again until a final species, the last men, are able to look back through time to tell the author the story.

Stapledon’s writing is very much of it’s time, slightly stiff and very formal, but his unique touch is to provide a spiritual and emotional weight that everyone else who has tried this grand-scale stuff has missed. Last and First Men isn’t just large-scale SF, but it also explores the smaller scale implications of evolution, genetic engineering, lab-grown humanity, horizontal genetic transmission (long before this was an observed phenomenon) telepathy and collective consciousnesses. There are few characters, save the author – one of the last men acting through one of the first – but the repeated visits to particular examples of the series of human species keep the story connected to humanity, even as the narrative soars above it. There’s every chance, I think, that it isn’t really a novel, and that Stapledon really was receiving transmissions from 2 billion years in the future.

It remains completely unmatched in imaginative scope and ability to actually pull it off – in marked contrast to some of the similar attempts to do grand evolutionary scale history. Last and First men is beyond compare – unless you compare it to Star Maker, the follow up. When Last and First gives us two billion years of the future, Star Maker gives the entire history of the universe from beginning to end and beyond including time spent with God in one of the best stretches of imaginative SF ever put to paper.

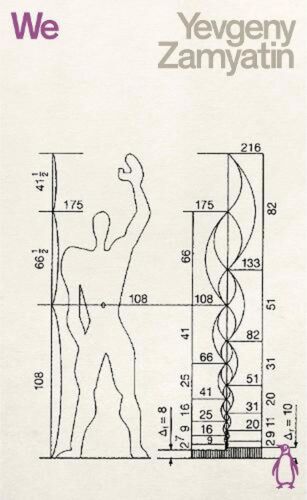

We, Yevgeny Zamyatin

One State is the perfect society. It is regimented, it is ordered, it is run according to the principles of reason, and all the buildings are made of glass so it’s nice and easy to keep an eye on each other. Citizen D-503 is enticed into his first, shocking acts of rebellion but life in the One State cannot possibly include freedom, and the state will get control sooner or later.

We is a fantastically grim, amazingly 1920’s book that has variously been said to inspire 1984, Brave New World, one of Ayn Rand’s terrible screeds and one of the most significant cultural outputs of the 21st century, the Sean Bean movie Equilibrium. We is very much the state as the ultimate oppressor, an entire society dedicated to protecting citizens from the mysterious outer enemy after a great war has devastated the population. As a reaction to the early stages of the Bolshevik revolution it’s a slightly panicked screed about what might happen (written 1920-21) that has survived both by virtue of predictive power and the fact that it’s really bloody good. The world Zamyatin creates is barely credible, but it’s still terrifying, rigid and morally, if not physically, possible, befitting the first of the bourgeoise Soviet Dissidents.

Don’t let the fact that a bunch of libertarian weirdoes have taken We on as an anti-communist rallying cry, because it’s not really about communism, in the same way that Naziisim is only part of what War with the Newts is about. We is about the terrifying reach and potential of the modern state, the apparatus that grew up around the end of the First World War that we’re still dealing with. The Panopticon was here, finally, with states that wanted to be deeply involved in everyone’s lives, and had the capability to do so. We captures that anxiety in one of the earliest forms, and the sparkling glass world of the One State still has the power to grip, 100 years on.

It’s written in the slightly ironic, sly style that characterises a lot of great Russian-language Scifi (Roadside Picnic springs to mind) and filled with maths references and stuff that’s so very Russian and of its time that there’s no way you could get them all – luckily, a good translation covers that one, and the penguin edition, with it’s beautifully designed cover by Jim Stoddart via Corbusier is a good translation.

Black Library Picks

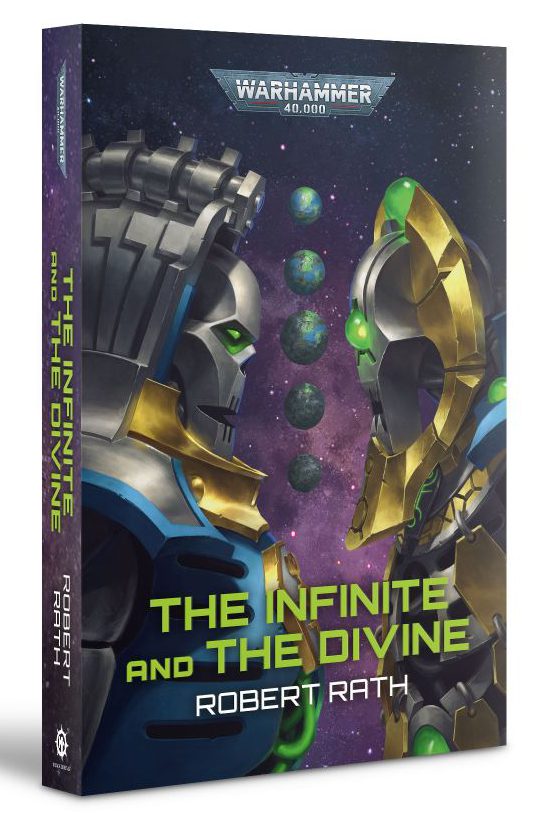

I look forward to writing these articles because one of the fun jobs is pairing up a Black Library book I’ve enjoyed with a bit of classic scifi that explores similar themes. Unless the theme is war and I’m just telling you about all the really good military scifi out there (read Forever War, already), that can be pretty tricky, but I like this one a lot. Today’s Black Library recommend is The Infinite and the Divine by Robert Rath. The Infinite (im not going to keep giving it the full title) is at heart a comedy about two immortal enemies who slowly become immortal…. well, friends is the wrong word, but certainly immortal acquaintances through playing tricks on each other, hanging out doing some cool science and creating increasingly contrived situations to deliver one-upnecronship via lightning, theft, witty banter, bizarre machines, alliances with destroyer cults and massive armies. Science Fiction comedy often really rubs me the wrong way, but Rath has two cantankerous old Necrons battling their way through time with a great deal of humour and still retains a deep pathos for their plight as immortal robots with nothing better to do than fight and delves in to what it means to be human and have friends along the way. It’s one of the better, and weirder, books to come out of the Black Library in recent years because it’s not the humour you’d expect, (fighting with occasional quips like some kind of grimdark Joss Whedon bullshit, but structural and situational humour that Rath pulls out of the concept he’s playing with.

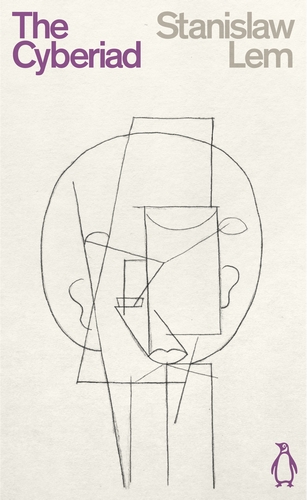

The pair for Infinite and Devine is Stanislaw Lem’s The Cyberiad, a tale of two cantankerous, immortal, creator beings spending eons creating, playing tricks on each other, going out on strange journeys, realising they’ve been duped and growing to be the best of friends throughout. It’s one of the great works from one of the absolute masters, and it’s also Lem’s funniest novel, working from a deep vein of absurdist comedy and wordplay to write a lot of daft slapstick humour across a comedic galaxy. It’s about what it means to be human, what it means to live in a society with people who rely on you, and what it might mean to be a robot – either figurative or literal – within a domineering society. The Cyberiad is made up of a series of short stories and vignettes that form a nice commute read or other short, bounded reading session as well, all ending with something either thought provoking or funny (or both), making it not just a challenging and interesting book to read but also a really pleasant one.

If you haven’t read anything by Lem, this might not be the best place to start – Solaris is just an impeccable piece of fiction that little can compare to – but it’s a very good example of his lighthearted works. The more I thought about this pair the more I wondered if Rath had taken inspiration from Lem in writing Infinite and Divine. Two cantankerous immortal wizard-robot stories ranging across time and space in a form of endless prestige competition? Seems likely! If he did, good on him – if you’re going to be inspired, be inspired from the very very best, which Lem most likely was. Lem is one of those authors who influenced the genre to such an incredible extent that it’s difficult to imagine science fiction without his input. There’s only a few of them there, you know, and most of the usually cited masters are, to me, fairly interchangeable. But there’s only one Lem.

Questions? Comments? Suggestions? Are you an American who just cannot believe I didn’t mention Hugo Gernsback even once, despite the fact that for some laughable reason he’s referred to as the “Father of Science Fiction”? Get in touch contact@goonhammer.com, or leave a comment below and join our Patreon and talk about books, please!