The Warhammer 40,000 universe is a massive place, and the “Narrative Forge” articles encourage thinking outside the box (literally) it comes to hobbying and narrative play. The aim is to make players more comfortable with narrative play and give tips and tricks for running campaigns. This week, Charlie Brassley is covering just about the one flavour of campaign not already covered by Robert “TheChirurgeon” Jones: Sandbox campaigns.

Sandbox campaigns are where you create a rich setting and then start a campaign with no rules or plan. They are the dumbest way of running a campaign. Absolutely riddled with pitfalls.

They’re also my favourite.

The classic campaign formats are classic for a reason: They provide structure and clear goals. We’ve previously gone over them here on Goonhammer. For your convenience, here’s a selection:

We haven’t talked about sandbox campaigns because they’re not generally a thing. Why? Because by definition you can’t systematise a campaign that’s deliberately avoiding campaign rules (beyond the standard 40K Crusade rules). This makes it extremely difficult to turn them into a sellable product. Moreover they need a group of people who are all on the same page, and keen on the sort of collaborative attitude more common in roleplaying games. Much as one still plays individual battle to win, one isn’t necessarily trying to do so in the campaign. You can’t really ‘win’ a sandbox campaign; instead, you’re trying to further plot, and to create memorable relationships between the factions. To systemise something like this would deaden it.

Fortunately, it’s perfectly possible to talk about it without giving you rules to follow. With that in mind, this post will cover:

- How to create your own sandbox

- How to run this kind of thing

- How to avoid burnout & other pitfalls

- An example sandbox

Table of Contents

Who are Sandbox campaigns best for?

This kind of campaign is best for a smallish group of players (certainly no more than 20) who know each other. There’s no minimum size – you can run these very happily with just two players. They are best for people who enjoy getting into the narrative side of things, but as long as every player will at least avoid doing anything explicitly anti-immersive, it’s not like everyone’s got to go particularly hard on the narrative stuff. That’s up to each individual player.

Don’t worry if you’re group has a broad spectrum of gaming experience; you won’t get the snowball effect you can get in campaign systems where there are rules-based consequences for success and failure (see: Necromunda).

Who are Sandbox campaigns not for?

If your gaming group tend to have even remotely fractious disagreements about any rules, that’ll be seriously amplified by doing something as vague as a sandbox campaign. Likewise if you’re not that fussed about narrative, this won’t be as exciting as a campaign system with rules to engage with. Indeed it might feel onerous if you don’t enjoy coming up with motivations and goals and so on.

Why on Earth would I choose this over, say, a map campaign?

The freedom. A well-designed map campaign (such as Goonhammer’s own Koronus Expanse) can integrate Battlefleet Gothic and other systems, even the best campaign systems will be, at some point, a constraint on the narrative. Those limitations are useful for ensuring an even playing field. With a sandbox, where the campaign side of things is collaborative rather than adversarial, no such constraints are required. Consequently you can freely flit between ground battles, kill teams, fleet actions and actual roleplay sessions without having to bodge rules for it. You just do it.

Creating the sandbox

Have a conversation

I’ll willingly risk coming off as a patronising asshole to make this point, because it’s so crucial: The campaign participants need to be interested in the same thing (Rob: I cannot agree with this point enough. Make sure whatever you’re doing, it’s what all the players want to be doing). You need to know what you all want out of the campaign, and you need to design it with that in mind. Ideally, most or all of the participants should have a hand in adding something to the sandbox, but at a minimum the primary author(s) should understand what the other players want. Here are some key considerations:

Length

With a non-systematised campaign like this, it’s best to agree on a period of time rather than everyone having to play a specific number of games.

The way my group manage this is that the broader campaign setting has no particular end point, but we’ll do discrete story arcs on particular things, usually over the course of a single weekend of intense gaming. In one instance, we did a whole week. Those stories started and finished, but left a mark on the ongoing setting and the factions’ relationships with each other.

Factions

It’s helpful to get an idea of which factions people want to play right at the start. There’s no point writing a world that has intricate political machinations between different Imperial factions if the players are all orks and tyranids, since they’ll never engage with all the juicy stuff you set up.

If, like me, you’re creating a sandbox that’s intended to run in perpetuity, then you need to know that right at the start, since you need to create a place that’s either big enough, or Macguffin-filled enough, to justify the arrival of unexpected factions.

![]()

Too many Imperial players? Have multiple armies!

A classic problem in running narrative things like this is having too many Imperial players. You don’t have to split everyone evenly into two sides, so it’s not as big of a problem as it would be in a more formal campaign system, but not a lot is going to happen if you have five Imperial players and one non-Imperial player.

My group’s approach is, if we’re collecting an Imperial army, to build up a non-Imperial force too. That way we alternate depending on who we want to play a game against. Even if you can just get 500-750 points of something sorted, we find it more satisfying than throwing our Imperial armies against each other. This has the added benefit of there being way more factions in the sandbox, making it feel more lived in.

When playing a campaign weekend with a focussed narrative, players will generally stick to one of their armies for that whole thing. As an example, there’s ten of us in our sandbox campaign, but four of us are getting together this weekend to do a mini-arc within the broader campaign, focussed on a conflict purely between eldar and orks. Three of the four of us have other armies, but those other armies won’t see the table during the upcoming weekend.

This wouldn’t have been possible if we hadn’t all made a point of producing non-Imperial armies.

Scale

Now that you know who’s fighting, you can have a think about how big a canvas you want. Note that scale is not the same thing as detail; you can put in a varying amount of detail regardless of scale. A small-scale sandbox would be a city, or perhaps a province on a planet. A large-scale sandbox would be a sub-sector or sector of space.

There are pitfalls with both small sandboxes (i.e. finding an excuse for all one’s friends’ armies to fight over a single city) and large ones (where one can mistakenly produce something with breadth but no depth, leaving the players uninspired).

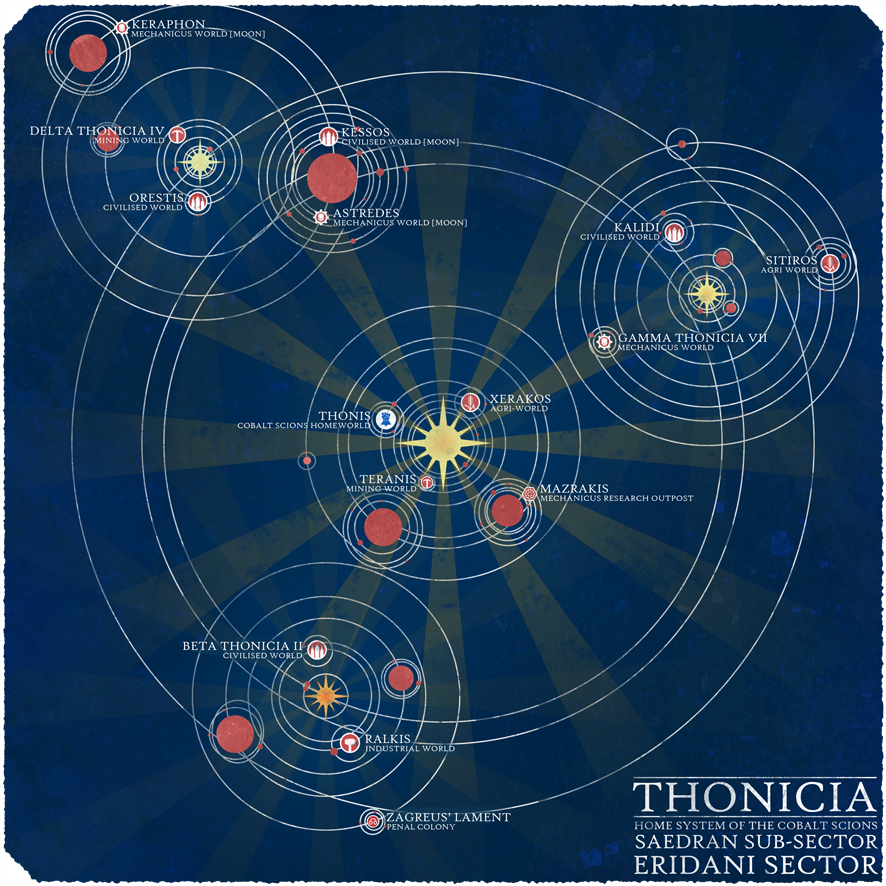

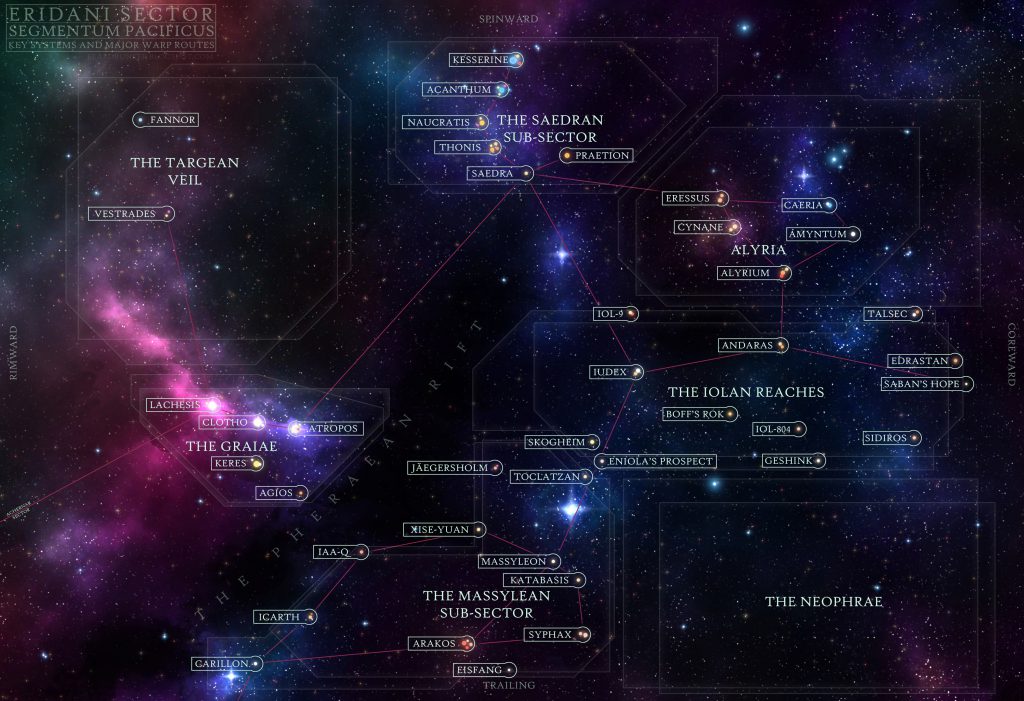

Our sandbox is a full sector of space. Why a whole sector? Flexibility. We deliberately keep some things vague so that if we need to invent a whole new star system to blow up, we can. We prepped it during the pandemic and started gaming in it in 2021. Since then we’ve fought plenty of one-off skirmishes and also some more long-running stories. I’ll return to that later.

Things to fight over

The angry factions of the 41st Millennium need little encouragement to go after each other, but it’s easier to come up with scenarios if you plant useful seeds. Here are some classic examples:

- A place with a precious raw resource, e.g. blackstone, adamantium & other rare metals, etc

- Useful infrastructure, e.g. ship or titan foundries, manufactorums using rare STC data, and more mundane stuff like promethium refineries.

- Navigational bottlenecks, be it a mountain pass, a key bridge, or a stable warp route in an otherwise tricky space.

- A place of cultural significance, like aeldari maiden worlds and Imperial shrine worlds.

Room to expand

Don’t be afraid to enlarge your sandbox if it suits your purpose. If you’re fighting over a planet, what other planets are in the same system? What’s the nearest system to it? Don’t forget, too, that you can expand in two dimensions: adding new areas, and adding new details to existing places. Cities are enormous, and a planet could have hundreds of them. Just wrapping your head around how much stuff of strategic import is in, say, South America will probably melt the average human brain.

Accept that you’ll create more than you use

This is a lesson learned by most creative people, and certainly writers and people who GM roleplaying games. Not every idea is precious, and you can’t predict what other players will latch on to. Make stuff up because it’s fun, and don’t worry about whether every last idea you have gets vigorously fought over in the ensuing campaign. They’ll either be the seed that grows a whole story, or a tiny detail that makes the world feel broader and more lived-in than the confines of the campaigns you fight.

Running the sandbox

GMs/editors

You may or may not want a GM for a sandbox campaign, but at the least it’s important to have one or more people who are on the same wavelength and have a coherent vision for the sandbox. 40K is a very broad church, but if you have one player who spends ages fleshing out a really granular city with interesting tactical features, and another player who plays a game of Titanicus in said city and casually decides that the city has now been flattened as a result of a random game they decided to play on Sunday, you’re going to have some bad feels. At the same time, you’re making a wargaming sandbox. Things are going to get blown up. Consequently, it’s a good idea to pick one or more people to be a sort of editor to run your ideas past, so that they can help keep things tonally consistent within the campaign.

Be willing to say when someone’s idea doesn’t fit

This is it: the biggest pitfall. Potential for some pretty awkward conversations here. In similar games (e.g. tabletop roleplay) one does one’s best to avoid cockblocking your fellow players, but sometimes people will come up with a dud, and need to be told. It’s also the reason why this format of campaign is played among good friends, since hopefully by this point you know how to disagree with them and provide constructive feedback.

In general terms, if someone suggests a location/character/mini-arc that just doesn’t fit tonally with what everyone else is doing, help this person see that by talking it through. See if the idea might be adjusted so that it works. Try to refine rather than discourage, but be willing to be firm if they’re in danger of ruining everyone else’s immersion by introducing something that just won’t make sense or be fun.

I’ve found it’s rare that this is necessary, but ultimately it’s why you put a GM/editor in place. At the same time, of course, the GM must regularly check they haven’t become a control freak who dislikes every idea they didn’t come up with themselves.

Make it accessible for your less creative friends

Just as you want people to feel welcome to contribute, and feel able to help shape a consistent storyworld, some people will be either too shy to share their ideas (at first) or are simply more interested in reacting to stuff that’s already been written. After all, why else would GW publish campaign books of their own?

This means it’s worth writing a variety of locations that speak to the various factions in 40K. It’s particularly worthwhile creating active warzones or small colonies; that way smaller forces could believably come and go (since either the colony lacks the means to stop them, or it’s a chaotic warzone where no one side has meaningful control).

It’s particularly helpful to write about a city or even a particular geographic feature people might fight over. Simply saying “here is Planet X, and people are fighting over it” won’t inspire anyone. Saying “Planet X has 4 major regions with promethium deposits named A,B,C & D, and two major space ports called E and F,” gives people something specific to fight a series of battles over.

Data management

Here it is: the sexy end of running a campaign. What other two words in the English language get the blood pumping so ardently? Data management. Hnnnng.

It IS really important though.

What I mean by ‘data management’ is somewhere to present everything you’ve written about the setting. As the campaign goes on, you’ll be updating that information as worlds and factions are changed by events.

This needs a format all the players can readily access, and that’s easy to update on the fly. Classic options include a Google Doc, since you can access that from any platform. Or, if you’re mates with someone technical like my friend Tom … make a wiki. This is of course more work, but much better organised.

You can check out said wiki here. Pages vary wildly from “here’s a placeholder sentence about a planet” to “here’s half a bloody novel.” It’s like a lucky nerd dip.

It probably goes without saying that the GM(s)/editor(s) will be the people mostly responsible for maintaining this lore repository. With multiple people contributing, it can get chaotic without someone keeping it organised.

Rob: I’m also going to jump in and remind everyone that our own Administratum is an excellent tool for campaign management, particularly if you’re using Crusade. Even if you’re not, Administratum lets you manage and track players, teams, rosters, campaign victory points, and other rewards, plus you can use it to create a campaign hub page with links to your wiki.

Arcs

If your sandbox is not so much a campaign as a persistent storyworld, you can have campaigns within campaigns, just like the Battle of Kursk was a (horrific) campaign within the (horrific) Eastern European Campaign of the wider (and horrific) Second World War. I’m referring to these mini-campaigns as ‘arcs.’

Playing an arc means picking a specific place/region within your setting, picking a goal for each faction, and spending a weekend battling it out. Here’s an example we played last year…

Example arc: A Simple Raid, With No Complications

Length: two weekends.

Players: 4

Games: personally, I played 10 games, mostly at 500-750 points, some at 1000.

The narrative context

An ork raid on Andaras Prime, a small Imperial colony, turns into a surprise four-way fustercluck. The planet has one major city, Orm Nabak, which Tom’s orks (da Two Worlds Waaagh) have attacked, and are now looting.

My space marines (the Cobalt Scions) are sent to help, and manage to kick the orks out of the city after a couple of particularly bloody games… which results in the orks going everywhere except the capital. Consequently, the orks start looting the ancient xenos ruins dotting Andaras Prime’s surface. This, in turn, exposes the presence of Drew’s Aeldari (Host Taliesin) who were stealthily hanging out in said ruins doing some light archaeology. Jeff’s genestealer cult (the Starborn Souls) have also been investigating these ruins, believing them to be the works of the star-father, and therefore sacred. Cue four-way carnage.

The factions and their goals

CHARLIE: COBALT SCIONS ASTARTES

– Get the orks out of the capital, reclaim the things they stole (including one of the city’s void shield generators), and force them off-world.

– Destroy the genestealer cult’s bases/nests, but don’t let them escape off-world.

– Force the aeldari to leave if they won’t go voluntarily. Diplomacy is an option, given the prevalence of other even worse threats.

TOM: BLOOD AXE ORKS

Take wot yoo can, give nuffink back! Specifically: keep the void shield generator we nabbed from the humie city.

DREW: IYBRAESIL CRAFTWORLDERS

Keep the other factions away from the ancient ruins long enough to complete our studies.

JEFF: GENESTEALERS OF THE STARBORN SOULS

– Our presence is revealed! Secure enough spaceships, and disable enough of Orm Nabak’s anti-ship batteries, to get off-world and start again somewhere else.

– Before we leave, glean as much as we can from the ruins left by the Star Father.

– Prevent the orks stealing or crippling assets needed for the evacuation.

How it went

The marines kicked the orks out of the city after an utterly pyrrhic victory. Actually this is a good example of how sandbox campaigns make you think about the broader narrative context; I was trying to prevent the orks stealing citizens, so had to stop any orks getting into my deployment zone to score. I just won the game on points, but was tabled in turn 5. So… why would the orks not be free to go and sack the city after the game? Tom and I took this technical defeat to mean that the orks had run out of time to nab captives before overwhelming Imperial reinforcements arrived.

Since we’d established the orks had stolen one of Orm Nabak’s void shield generators prior to my arrival, I set about trying to get it back. We played several scenarios near the ork landing site as I attempted to scout out Tom’s grounded ship, gathering clues as to where precisely said shield might have been taken. Turns out it had been taken into his vessel. Shit. I attempted an all-out assault in a subsequent game, but finished said assault with nowhere near enough dudes standing to mount a serious boarding action. Ahh, the ignominy.

Next came the attempt by Jeff’s cult to escape off-world. We played a scenario in which the objectives were two defence laser silos, and the two reactors powering them. If Jeff could control a majority of the objectives, I’d be unable to stop his ships as they made their bid for freedom. If I controlled a majority, the evacuation would result in almost no survivors. In the end, we drew. Half of Jeff’s motley assortment of freight lifters and shuttles were blown out of the sky, but the other half got away. Note the cooperative nature of these end-states: none of them explicitly wipe Jeff out entirely, even though that’s what the Imperium would want, because we don’t want to have him be unable to play games!

This is of course a limitation of 40K Crusade in general rather than sandboxes; you get a Marvel-like quality to characters and/or armies that just won’t die. If you aren’t playing Crusade, you can of course use your miniatures to represent a variety of characters, any of whom can die. Assuming you are playing Crusade, though, the trick is not to make the stakes about killing the other guy – you’re always doomed to failure there – but about progressing the relationship these various characters have to each other. This was reflected by the relationship between Tom’s warlord Guluk da Git and my poor Lieutenant Antigonus Nerva, who Guluk absolutely slapped in a succession of battles. Over time Nerva’s repeated beefings resulted in getting high-end bionics, a force field, and other relics designed to reflect his time in the School of the Hardest Knocks. Eventually he became tough enough to attempt a (somewhat foolhardy) operation to assassinate Guluk. Again, obviously, I couldn’t really kill Guluk, but I did manage to lay him low and give him a mean battle scar. Guluk suffered from it for a few battles, and henceforth might take ‘Lefftenunt Nervous’ a bit more seriously. Maybe? Point being, those two characters now have history. When they face each other on the field it has meaning. That would be true whether or not you’re playing a sandbox campaign, but with a sandbox, it was that much simpler to just pick a scenario we felt reflected the emergent narrative, and then resolve it.

The weekend as a whole was great. Drew and I ended up forming an aeldari-Imperial alliance of convenience. While Jeff’s cult was dealt some heavy blows, they did ultimately manage to escape with a limited number of ships to go forth and spread their seed across the sector (ooooops). And while Tom’s orks were eventually booted off-world, they did so with a cargo hold full of swag, so it was a win from their perspective. Checks out; orks is never beaten.

How to write an arc

1: Establish Participants

Start by finding out who wants to play, and when. Then figure out which armies everyone’s going to use. This is where the benefit of each player having access to multiple crusade armies really shines.

2: Pick a location within the sandbox

You’re generally going to want a single system, planet, or even city if you’re just playing for a weekend.

3: Do you need to expand the lore of your chosen location?

If you’re fighting over a bit of your sandbox that’s little more than a name on the map, now is the time to add some extra detail to help inform scenarios. What are its major exports? Does it have any unusual geography? Who lives there? What defences and infrastructure does it have?

4: Decide on some goals

Your goals will probably emerge from the steps above, particularly step 3. Each faction will have its own goal, and it can be as specific or as broad as you like, but I’d err toward the specific. In the example of Andaras, my wanting to retake stolen Imperial technology from a grounded ork ship was a specific thing to build scenarios around. That gives you recon, penetrating the outer defences, and possibly a boarding action, all from one goal. That’s much easier to choose scenarios for than “beat the orks, I guess.”

5: Adjusting course

Once the mini arc’s underway, events on the table might conspire to render your goals moot. That’s fine! Decide on what your warlord will do instead, even if it’s just “escape this situation with as many survivors as possible.”

6: Decide on the consequences

You can decide what you think the consequences of an individual game will be before you play it, e.g. “if you blow up my fuel depot, I won’t be able to use my tanks in the next game.” You can then finesse this after the game, e.g. “you only blew up half my fuel, so I’ll use fewer tanks in the next game,” or “each of my tanks will only have enough fuel to move three times during the game.” Of course, the consequences needn’t have in-game effects; for me they rarely do. Destroying a fuel supply could mean the end of one faction’s offensive ambitions in a theatre. It could be the final game you play in the weekend, with the one fuel dump scenario you fight being emblematic of how multiple raids go.

For an arc as a whole, each game is played as a step on the way towards (or away from) each faction’s intended goals. You’ll generally know how many games you’re going to get done in a weekend, and what size of game you want to play, but you don’t have to constrain yourself to the final battle being the thing that decides the success of a faction’s goals. It might be that after two disastrous defeats it’s clear a goal won’t be achieved, at which point, it’s more interesting to pivot to evacuation, orderly withdrawal, or whatever else. History is full of leaders saying they’re going to do X, then having to change their plans when reality slaps them right in the specials.

Pre & post-game process

What’s my motivation for this scene?

Your first step is to decide why the battle’s being fought. If previous events don’t suggest an obvious battle, you could always roll off, after which the winner decides how he’d like to attack the other player. The two most obvious things to go for are lynchpins and logistics. Other classics include personal vendettas, which would suggest assassination missions or similar.

Lynchpins

Your forces are attempting to destroy or break through a particular point in the enemy defences. This could be a weak point in the enemy lines, or maybe a vital bunker complex, or perhaps a key orbital weapons battery preventing the bulk of your forces landing on-world.

Logistics, logistics, logistics

You are attempting to steal or disrupt your enemy’s lines of supply. This could be a raid on one of their supply depots, an attempt to sabotage a key bridge, or ambushing a convoy. Honestly this is one of the richest veins to tap, and can be overlooked in a storyworld full of shooty-death-kill. Maybe it’s my inner Ultramarine talking, but if in doubt, think about supplies.

Pick a mission

This is fairly self explanatory, but it’s worth emphasising that generic missions are extremely adaptable; don’t feel constrained by their names. The generic Incursion-level mission Supply Cache is a good example of this; it’s really just a game with four objectives. That can be adapted for a huge range of situations without changing the rules.

There’s one small problem with picking missions: the GW design studio have absolutely gone for quantity over quality; some of the missions in the mission packs are great, some of them are fundamentally broken. We’ve found it’s worthwhile for your group to get a shared spreadsheet going with your favourite missions, with additional notes about what narrative contexts for which you might use that mission (e.g. “Supply Cache – generic progressive 4-objective mission. Contexts: supply raids, claiming/defending territory.”)

If you’re a bit stuck for ideas, then there’s plenty of them in the various Crusade mission books… it’s just that the rules don’t always work as intended. When you’ve got a bunch of missions you enjoy, feel free to take the theme of another mission, and just use that as your narrative context for a more generic set of mission rules.

Agree on the consequences before you start the mission

This is the narrative equivalent of playing by intent. You don’t want to lose a game and for your opponent to assume this means s/he’s kicked off a whole planet, where you were imaging milder consequences. Just like measuring charge ranges, if you agree before the event, things tend to be smoother.

Examples:

- If the orks are crushed in this ambush, the eldar will be able to track the survivors and learn the location of their base.

- If the Imperial Fists disable this orbital battery, we’ll fight the next game in the city at the gates to the corrupted governor’s palace, since there’s no way of shooting down their thunderhawk. If they lose, the next battle will be on the approach to the city, as they’ll have to approach on foot and fight their way through the city to get to the governor.

Post-game: finesse the consequences

If in-game events have made your agreed outcomes seem not quite right, have a chat post-battle about what this could mean. If you need to change the agreed consequences, make sure it’s something both of you think makes sense, and/or makes things more interesting.

Maps: how & why

This is a whole topic on its own, and it deserves its own article, so I’ll be brief. Sandbox campaigns don’t technically need a map, but as with most campaigns, a map can really help inspire scenarios and plot arcs in ways that a list of planetary systems really won’t. This begs the question, “How make? It hard.”

There’s several approaches. With each of them, you can be as detailed or basic as your inclinations dictate. You can just draw or paint something on some paper, then scan it or pin it to the wall of your nerd cave as appropriate. Quick, free, simple. You can always add more detail as you go.

My usual preference is to make something digitally, usually in Photoshop. There’s also https://www.photopea.com/ if you want a free alternative and don’t mind the reduced convenience. The other approach is to use map making software like Wonderdraft or whathaveyou. These bespoke softwares tend to be more focussed on making fantasy maps rather than sci-fi, since they’re often made with the fantasy roleplay market in mind. I’ve used and enjoyed them, just not for making 40K stuff.

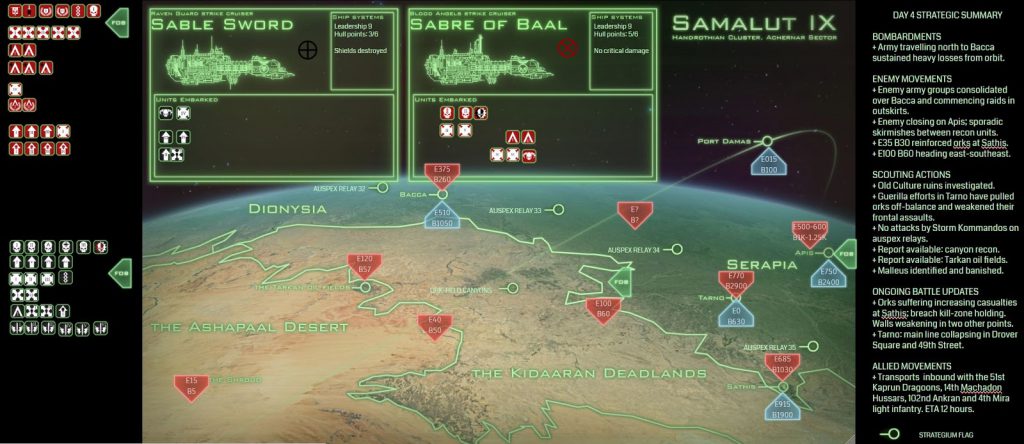

The zenith of cartographical joy is to make an interactive map. This might be using a physical plastic map like the old Planetary Empires thing GW made, or by having a cork board and coloured pins. If you’re going digital, there’s a few approaches here. If you want the players to be able to move icons around on the map (like a digital version of pins on a cork board) then import your map into a Google Drawing as the background image. Next, make smaller images for icons showing factions and armies. If you want non-rectangular icons remember to create the images as .PNGs or another format that supports transparency. If you don’t need moving icons, and you have a friendly neighbourhood internet champ, then you could make a hyperlinked map and connect it to your campaign wiki.

Which method did I use?

All of the above, at various points. I’ve found the Google Drawings option particularly great for small-scale stuff set on a single planet, as with the Samalut IX campaign I ran a few years ago. You can read about how I made the map here, and how it worked with the campaign turn sequence here. An example from the campaign can be seen below. It’s showing the deployment phase of the fourth campaign turn… this wasn’t a sandbox campaign, it was a roleplaying wargame, but that’s another enthused diatribe for another day.

Avoiding burnout & other pitfalls

Being unwilling for your faction to take consequential losses

Since there’s no set structure to sandbox campaigns, and since 40K Crusade is so forgiving, the only person in a position to give your army a meaningful setback is you.

It’s best to put a little skin in the game; in a recent clash with a regular opponent’s Drukhari, we decided he’d captured several members of my heroic-level hellblaster squad. Later this evening, as I write this, I intend to play a rescue scenario. If I lose it, I intend to knock the squad back down to blooded, or possibly reset the whole unit and have the grief-stricken sergeant have to start again with a new crop of lads, knowing his brothers are probably still alive and in impossible torment. It’ll make the battle far more meaningful than just a random game of 40K. That’s a relatively small consequence. Bigger ones could come when we decide to fight over my chapter’s home planet, itself situated within our sandbox!

Excessive enthusiasm for blowing everything up

There’s the opposite problem: the player who thinks the most interesting narrative consequence is to destroy everything! Calm thyself, Shiva. Star Wars Episode IV isn’t exciting because the Death Star blows up (haaaa, spoilers) but because the Rebels are deep, deep in the shit and manage to pull through thanks to Luke’s realisation that the targeting computer was pure betrayal (plus Han’s timely intervention). Change is usually more interesting than complete destruction, and sometimes trigger happy players need to be encouraged to go the extra step when planning the consequences of their battles.

Know how to collaborate when competing

There’s no point playing a PVP game if one or more of the players are trying to lose for narrative reasons, and at the same time, there’s also no point playing a sandbox campaign if your intention is to win hard and win constantly.

Not to sound overly wanky (too late?) but during the pre-game chat about the consequences you’re aiming more for a writers’ room, figuring out nice juicy plot twists. With the consequences agreed upon, you’re free to try and slap out a win during the game (within reason).

Avoiding burnout

Traditionally the most important way of avoiding burnout is to agree on timescales, and have a set number of weekends/play sessions/battles in which to conclude either your campaign, or a story arc within your giant indefinite sandbox. People have to be able to set their expectations about pacing, so if you can’t do that in the long term, do it in the short term. We’re a very short-termist species, after all. Glances despairingly at current affairs.

An example sandbox: the Eridani Sector

I’ve been mentioning and linking to this throughout, but I thought it would be helpful to explicitly talk about the thought process behind designing this bit of space. I won’t slavishly present you with all the info on the setting; the wiki does a better job of that. This final bit is about the planning process.

The fundamentals

It shouldn’t all be Imperial

The Imperium isn’t meant to be one contiguous blob, because space is too big for that to meaningfully work. You can’t meaningfully have a battlefront in space, neither at the sector level nor at the system level. The official lore often reflects this, describing how the Imperium is both vast and stretched thin. As such, I decided that the nominally sector would contain ork worlds, eldar colonies, a little tau enclave, multi-species pirate dens, worlds long held by the forces of Chaos or necron dynasties, and anything else we fancied.

Make a conceptual list of the sort of places you want

I wrote down some basic ideas, like so:

- The Massylean & Saedran sub-sectors: well-established Imperial presence with all the classic ingredients like Mechanicus worlds, hive worlds, all that stuff.

- The Neophrae: a mysterious sub-sector that has, thus far, swallowed the Imperial expeditions sent in to chart it. Fertile ground for future campaigns of colonisation and conquest, and open as to what’s in there. Necron dynasty? Exodite cluster? Chaos empire a la the Sabbat Worlds? Basically, whatever we want when the time comes.

- Alyria: a nominally Imperial sub-sector that’s not too fussed about the Adeptus Terra, and which is constantly at war with itself. Potential for different Imperial factions to end up on opposite sides of a dispute if anyone fancies an Imperial civil war, or indeed fertile ground for the followers of Chaos to corrupt one side via their desire to dominate ancestral enemies.

- The Targean Veil: a largely uncharted sub-sector with just one Imperial mining colony in it. Plenty of potential for xenos players to get a bit of an empire going before the Imperium expands rimward.

- The Graiae: a small Imperial-dominated sub-sector with a higher than normal expression of psychic potential; leaves the way open for Ecclesiarchy-based conflicts and/or an epidemic of witchery.

- The Iolan Reaches: a frontier-style sub-sector with small isolated Imperial colonies trying to get by whilst intermingled with xenos worlds and endemic piracy. In the early stages of the campaign, when everyone would still be building up their armies, this felt like a place ripe for endless skirmishes. As our armies grow, so too can the scope of the conflicts, until whole sub-sectors are being invaded by massed battlefleets.

Block out those places on a map

The next step was to make a map. I wrote about the process of doing so over at the Beard Bunker.

The key thing about making a map is to get inspired as you throw details in. When I ended up with a dark rift running diagonally from the bottom left corner two thirds across the map, I thought it’d be interesting if this was some sort of navigational obstacle. I called it the Pheraean Rift and heavily implied in the lore that it was a Necron Pariah Nexus, but didn’t set it in stone in case people wanted to do something else with it. Sure enough, Andy had his necrons infest the place, and was soon raiding the rimward border colonies of the Massylean sub-sector in a series of battles against Tom’s Raven Guard.

Let the map develop over time

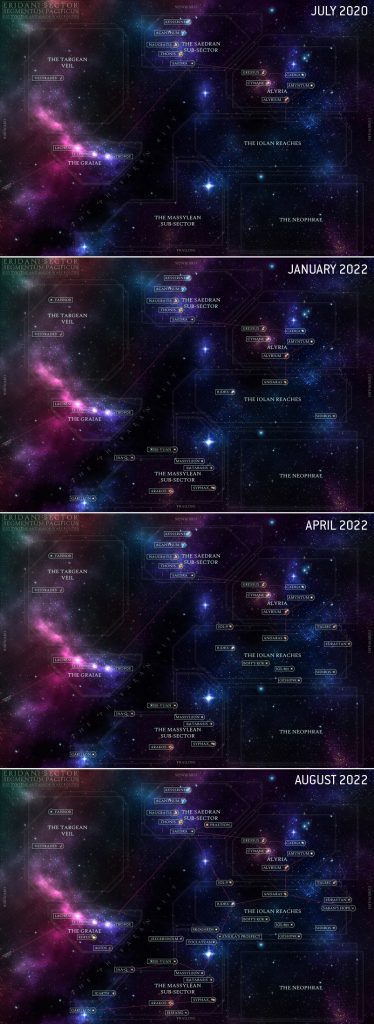

Here’s a series of images showing how we added systems to the sub-sectors over time. By establishing a rough flavour for each region, it was much easier for people to come up with planetary systems that made thematic sense.

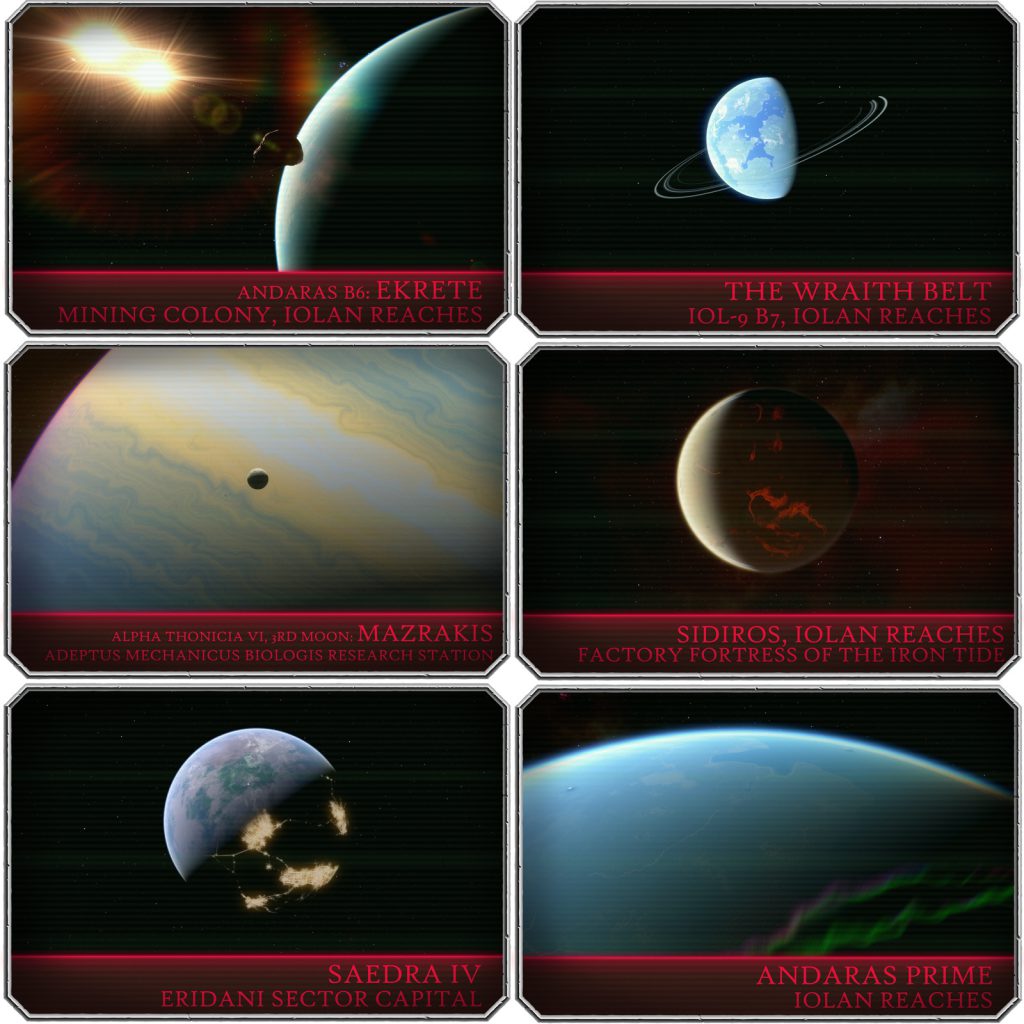

Make illustrations (if you can be bothered)

If you’re keeping a lore repository, it can be nice to spruce up your locations with images. I don’t have the time or skill to do full-on illustrations, but I did use SpaceEngine (the procedurally generated universe simulator, available on Steam) to capture suitable images for a number of worlds.

Story arcs

In addition to one-off games, we’ve now had a few self-contained arcs as well. I already mentioned the Andaras Affair; there was also a mini-arc between the orks and the eldar in which my Goffs were unwittingly instigating a drukhari invasion. Each of these arcs was played out by groups of 4 players over a single weekend; usually just 2-4 games each. In the case of the farcical Gateway to Hell we knew we’d have time for two games each on the Saturday, followed by a 2k-a-side doubles game on the Sunday. We ran it much like a ladder campaign, i.e. whichever side won a majority of games in the preliminary skirmishes got to define the situation going into the big doubles game. In the end, the eldar absolutely pounded the orks, but the final forlorn charge was so glorious I ended up writing an orkish version of The Charge of the Light Brigade, because I am a serious person with impeccable priorities.

In future we’re keen to do meatier arcs, particularly revolving around first a substantial Chaos invasion, then after that an ork waaagh!

For both of those future events we’ll probably have players who have armies on both sides of the conflict, which means anyone can play anyone, and also emphasises the non-competitive attitude of our player group, at least at the campaign level. We still play individual games to win.

Final Thoughts

The dumbest, and the best. Your mileage probably varies. If you’re keen to do something like this yourself and have questions, or if there’s narrative 40K content you’d like to see more of, give us a shout in the comments below, or email contact@goonhammer.com.